Sea Change — Indigenous Women

Leading the Way

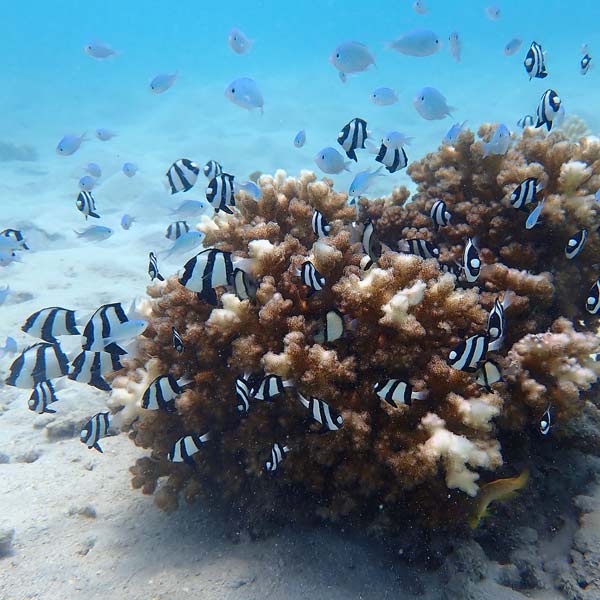

Though Wyoming’s closest coral reef is, well… more than a few miles away, protecting these vital ecosystems is critical to the entire planet. Not only do healthy, thriving reefs provide storm breaks and mitigate erosion of seaside lands and communities, but they are also home to a staggering amount of biodiversity. Coral reefs house more species per unit area than any other marine environment — including about 4,000 species of fish, 800 species of hard corals, and hundreds of other species. And those are just the ones researchers know about so far! Experts estimate that there could be millions of undiscovered species of organisms living in and around reefs.

In addition to being critical to the overall health and biodiversity of the planet, these precious marine ecosystems are integrally important to the Indigenous communities that live in their vicinity. These communities, unfortunately, are also experiencing some of the most intense environmental degradation and damage with few programs and resources to stop it. Marine scientist Dr. Andy Lewis witnessed this dynamic first-hand as an eco-tourism director on the True North, an Australian luxury cruise vessel.

“In that time we used to circumnavigate New Guinea, and then the vessel would be in Australia in the dry season. Then in October, we would take it to Indonesia, and then all around the waters of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. I did that for 11 years,” Dr. Lewis recalls. “And by about 2017, I realized a couple of things: firstly, that there were a lot of really, really good reefs still up there: ultra-high biodiversity, really the last great chunk of really high biodiversity reef left in the world. Secondly, no one was really doing anything substantial up there in terms of marine conservation in the remote islands that needed it most.”

With a vision of protecting these fragile reefs, Dr. Lewis founded the Coral Sea Foundation: a nonprofit dedicated to researching and preserving the thriving reefs around the region. His work soon led him to a fascinating observation. “There is not a government capacity for doing marine protection stuff in those countries. They're some of the poorest countries in the world. The only way to get stuff done there is actually to engage the local people. I realized that about that same time that it was usually the women in the villages — particularly the younger women — that were really passionate about marine conservation and were the ones that were always coming and asking me what they could do, how they could get involved. I realized that about 80% of the students studying biology at the University of Papua New Guinea were women. So there was this incredible pool of educated, smart, passionate women coming through that were desperate to get involved in marine conservation. But, they didn't have many opportunities to do so,” he recalls.

Dr. Lewis seized the opportunity to empower these driven Indigenous women to take action and dive into the conservation work that nobody else was doing. Slowly, he began to assemble and educate a team that could begin fieldwork around the islands and reefs of Melanesia. “I realized that there were just a lot of threads coming together there. As you probably know, if you empower women in developing countries, it achieves a whole suite of things at once. Birth rates come down, domestic violence rates come down. Everyone's health improves: maternal health, infant health, and generally better decisions get made about managing natural resources if women are involved. So that was why my first thought was, why has nobody done this before? And the second thing was okay, I'm just gonna listen to what these women want and try and try to empower them to do the work that they themselves want to do.”

So it began: the first organization of its kind, run entirely by Indigenous women, fearlessly blazing a trail toward conservation goals in one of the poorest, most dangerous sections of the planet.

A couple of years in, just as the Sea Women of Melanesia program was gaining momentum, the pandemic struck. Dr. Lewis and his team were no longer able to set out on expeditions together — he could only advise and mentor from afar, and encourage the women to launch and run their own research expeditions. He wasn’t at all surprised when they rose to the challenge. It was at this moment that the Hughes Charitable Foundation learned about the heroic efforts that the women of Papua New Guinea were making, despite an array of challenges, to protect their natural resources as well as care for their home communities.

“They've been doing fantastic work. They've just been out doing the hard yards. They've been engaging the communities. They've been delivering water tanks and humanitarian aid into the villages. They've been surveying the reefs to try and get the management plans to get the marine protected areas that the people want,” Dr. Lewis says. “One of the main things that the women asked us for was period products. They said, ‘Look, we've got no pads here. Sometimes we don't even have underwear; can you please send us tampons and pads?’ And we said, ‘Hey, look, we can do better than that. There's some really good, sustainable stuff that we can get up to you now. So we've done a deal with an amazing group down here in Australia that makes these beautiful, sustainable period pad kits out of recycled fabric.”

Last year, the Sea Women of Melanesia was recognized by the United Nations — The Champion of the Earth Award was granted to the team in the category of Inspiration and Action. “That's the biggest environmental award in the world,” Dr. Lewis emphasizes.

The momentum continues to grow, he explains, largely because of the women’s dedication and leadership. “We're now looking at trying to replicate the model and roll it out to a number of other really high priority locations in Papua New Guinea. There's at least another five locations where we would like to have a regional office.” Another chapter is taking shape even closer to home for Dr. Lewis. “Now we're starting to be contacted by members of the Indigenous community here in Australia. The Aboriginal people and the Torres Strait Islander people, and they've come and said ‘We've seen what you guys are getting done in Papua New Guinea. Can you come and help us? We'd like to do something similar down here.’ So we've just kicked off the Sea Women of the Great Barrier Reef Initiative.”

“We’re so impressed and inspired by the Sea Women program on multiple levels,” says Molly Hughes, Executive Director of the Hughes Charitable Foundation. “Putting Indigenous women in a position to lead and drive important decisions around their communities and natural resources achieves so many things. And ultimately, their research and conservation efforts will help to protect an ecosystem that’s fragile and vulnerable. This is a model that we believe can work not only in Australia but across the globe to bring more Indigenous voices and power to decision-making around landscape management.”

Zillah Midire is from Port Moresby and studying marine bio at JCU Townsville after following her passion and quitting a 10 year career as a graphic designer to come and study marine science. She has done a number of training trips with us on our dinghy "Pip" at Maggie, which was partly funded with the HCF grant (middle).