Not Forgotten, Not Erased

Some counties have rates of murder against American Indian and Alaska Native women that are over ten times the national average.” — United States Department of Justice

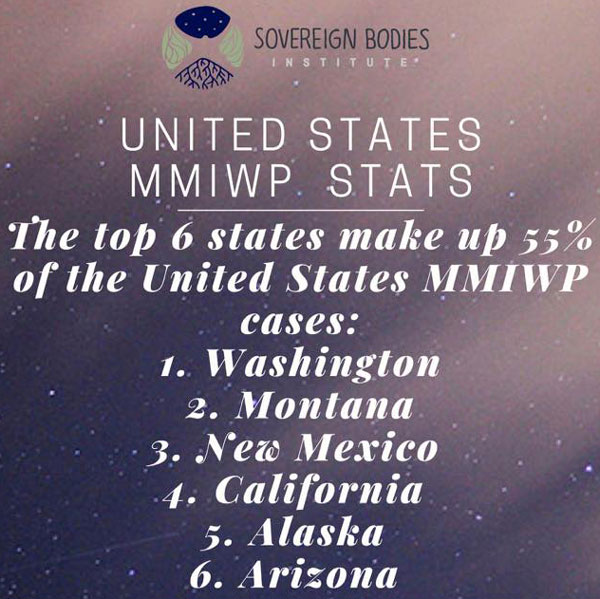

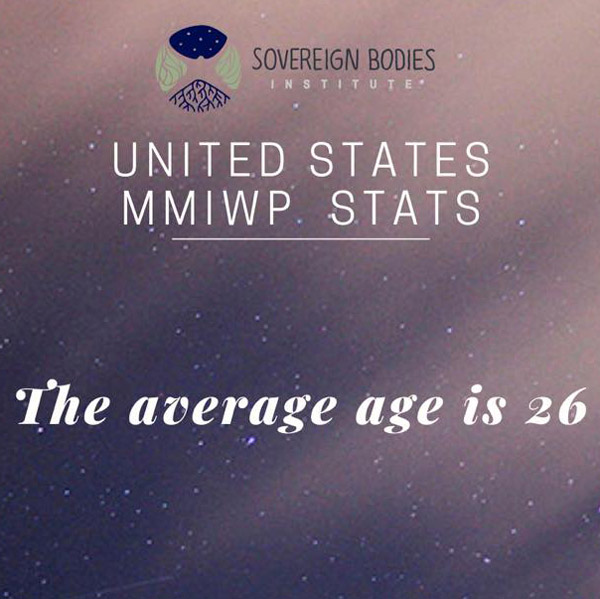

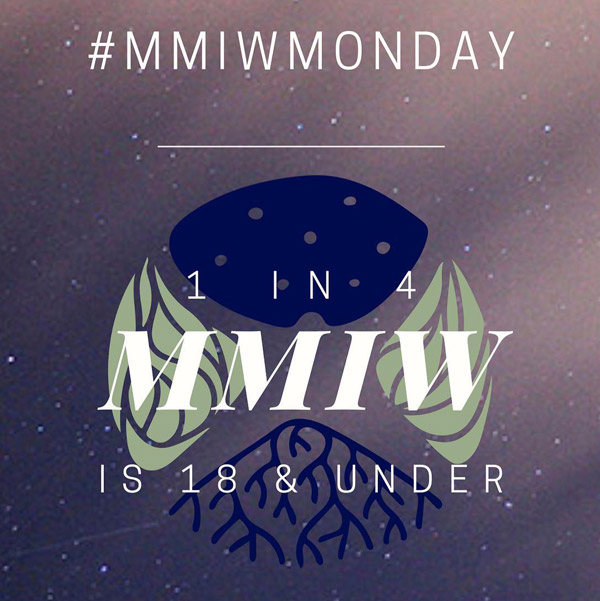

The statistics that continue to emerge around the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People* are truly shocking. The rates of violence against Indigenous individuals — largely women, girls, and two-spirits — are exponentially higher than those against many other groups in the United States and Canada. What’s more disturbing, however, is the fact that these numbers represent only a fraction of the incidents of this kind. As we all cultivate a deeper understanding of this problem, a couple of things have become clear: the established systems are not adequately protecting Indigenous people, and a compassionate, innovative, and culturally-informed approach to a solution is critical.

“I am absolutely in awe of the work that Sovereign Bodies Institute is doing in this arena,” says Molly Hughes, Executive Director of the Hughes Foundation. “They’re inspired by their own experiences with violence against Indigenous people, and uniquely poised to do this amazing work.”

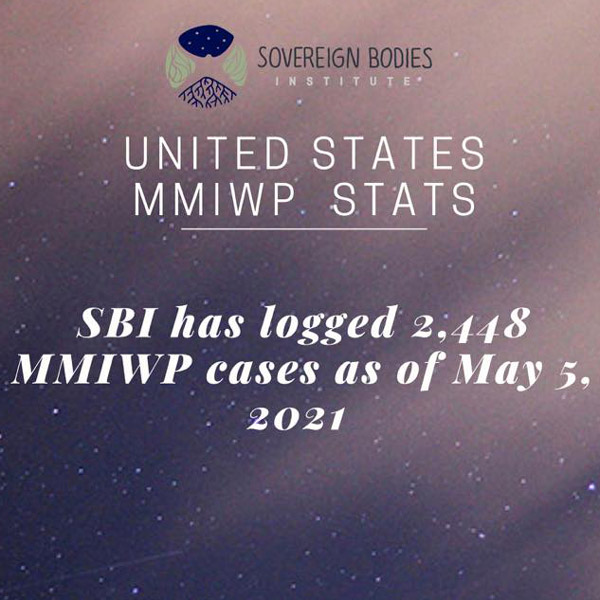

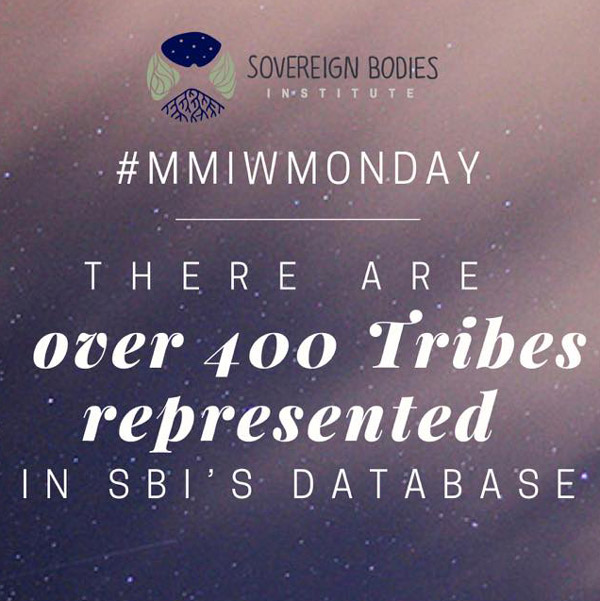

The Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI), based in California, has developed a groundbreaking three-pronged model to combat the pervasive problem of violence and trauma inflicted on Indigenous people. First, SBI developed and maintains The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits Database: the first-of-its-kind log of cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people, from 1900 to the present day.

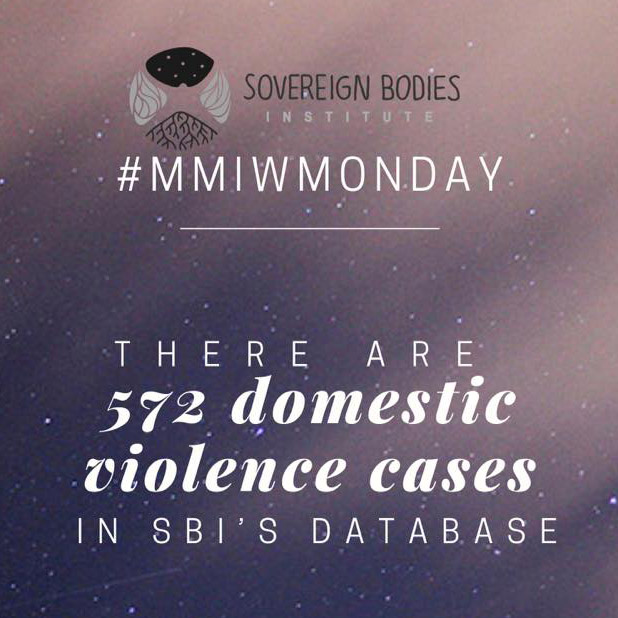

“There are many lists and sources of information online, but no central database that is routinely updated, spans beyond colonial borders, and thoroughly logs important aspects of the data, and overall, there is a chronic lack of data on this violence,” explains the organization’s website. “The Database works to address that need, by maintaining a comprehensive resource to support community members, advocates, activists, and researchers in their work towards justice for our stolen sisters.” SBI compiles all relevant data on cases including the victim’s name, Indigenous name (and translation), age, family information, any perpetrator information, location data, and any details on the incident and law enforcement and/or government response.

“SBI is a research and services organization that really began when our founder Annita Lucchesi — who is a survivor of multiple types of violence including human trafficking — felt called to catalog, to inscribe this truth, of people being disappeared from their communities and from their land. And at the time, it wasn’t being tracked, so it turned into our database,” says Mox Alvarnaz (Kanaka Maoli), Outreach Coordinator for SBI. “There was this urge to collect the truth and not have that forgotten or erased.”

In addition to compiling the information in The Database, SBI conducts ongoing academic research on issues that are interwoven throughout the fight to protect Indigenous individuals, communities, and lands from harm. But as their efforts to collect information grew, it became quickly apparent that the families of those missing and murdered people needed support on their journeys as well.

Our services component is not divorced from our research,” explains Alvarnaz. “Our research improved when people’s needs were met. People need to trust us and feel connected to us, and know that we’re responsibly holding their stories in a good way, and are going to be there for them. We’re not just pulling knowledge out of their suffering. We are here to materially be a part of their lives and communities, which are often our own communities, relatives, and loved ones as well.”

“You can only hear so many families tell you that they can’t make an interview with you because they don’t have gas, because they had to go grocery shopping, before you think, ‘What am I doing here?’”

Alvarnaz continues: “There is a necessity — families were telling us that they had immediate needs for food, for diapers for the children whose mothers are missing, that those needs needed to be met. As the holders of those stories, we have an obligation — a responsibility and a duty — to try and meet those needs.”

“Let’s feed the people, let’s get people returned home, let’s get the families what they need,” Alvarnaz summarizes. The dynamic team at SBI isn’t only guided by their interactions with the families of missing and murdered people; many of them have first-hand experience with violence. “We’re researchers, but to my knowledge, everybody that I work with at the organization, our leaders are all survivors of domestic, gendered, sexualized violence or human trafficking,” says Alvarnaz, who is a survivor of sexual and domestic violence.

And while the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People is beginning to gain some momentum in the mainstream press, Alvarnaz is often disheartened by the way the stories are told — too frequently, the voices of those living and working in the heart of this epidemic are eschewed for splashy, sensationalist coverage. Meaningfully addressing this problem (and others), Alvarnaz says, requires an understanding that this problem is far from new. In fact, it’s rooted in generations of settler colonialism and the current continuation of genocide against Indigenous peoples.

Since contact, the empire has sought to disrupt our ways of living, existing, and perpetuating ourselves as Indigenous peoples,” says Alvarnaz. “When people ask ‘When did this crisis begin?’ my answer is, from the point of contact.”

An essential element of the violence against Indigenous people in this enduring system of settler colonialism is the idea of a gender binary. “The empire sees two kinds of bodies — men and women. Women are to be consumed and subservient and vulnerablized, and men are a threat, and so must be neutralized. The empire works to restrict Native bodies into two gendered roles, but in truth, all Indigenous bodies are regarded as a threat to the empire.” Two-spirit and gender-diverse individuals are often healers, spiritual leaders, and the carriers of historical knowledge in Indigenous communities, which is a large reason that settlers sought to enforce their idea of gender. “Gendered roles exist to erase our complexity and justify various violences committed upon our bodies,” reflects Alvarnaz, who is a third gender called “mahu” in Hawaiian society.

“I feel like this is the part of the conversation that’s really left out. If you open up any newspaper to hear about MMIW, there’s this casting about of ‘Where are the native women going? Who’s doing this terrible thing? Why isn’t anyone doing anything about it?’ In reality, that conversation is completely divorced from the issue’s ongoing history.”

Alvarnaz recognizes that the current mainstream media coverage surrounding MMIW is imperfect in describing the legacy and complexity of the issue, but it gives a wider audience a way to begin to engage and become allies. “It’s a way to describe a gendered experience of racial danger, as well as the bureaucratic forces we’re forced to participate in as we search for healing, closure, and justice.”

“Especially as we spend time this month learning about and honoring our Native American community members and their wonderfully rich heritage and cultures, it’s important to keep this ongoing violence in mind,” says Molly Hughes. “It’s not enough to simply be aware that this kind of violence is so pervasive. We must support organizations like Sovereign Bodies Institute that are doing such impactful work on so many levels to bring an end to this terrible crisis.”

*This epidemic of violence is also known as “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women,” and “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits,” though each of these specific titles has particular semantic limitations. None of them are considered inappropriate, but different groups will utilize them as they find most in alignment with their cause.